By Mark Ellis, November 9, 012 in Godreports

|

| The Raising of Lazarus, 1890 |

A record 1.2 million visitors came to the giant retrospective of Van Gogh’s work in Amsterdam in 1990, which coincided with the 100th anniversary of the Dutch post-Impressionist’s death. What visitors did not see at that major exhibition were van Gogh’s Christian-themed paintings, which were left in the basement of the museum.

“None of the religious imagery was in the show. It was deliberately kept in the basement,” says William Havlicek, Ph. D , author of Van Gogh’s Untold Journey (Creative Storytellers). “In Western art there has been a move toward secularization through existential thinking,” he notes, which followed the disillusionment of many artists after two world wars.

Havlicek spent 15 years researching and studying more than 900 of van Gogh’s letters. His revealing book dispels many of the myths that surround the painter’s tumultuous life. “Vincent’s letters portray a very different story than the popular tale of the mad artist who cuts off his ear,” Havlicek notes. “What emerges instead is a story of selfless loyalty, the epitome of the Gospel’s sacred counsel—‘love one another.’”

“Many of his religious letters were held back and only released in the last five or six years,” Havlicek adds.

Vincent’s father and grandfather were pastors and it seems many in the van Gogh family gravitated toward religion or art. His father Theodorus – a Dutch Reformed minister — was not known as a compelling preacher, but a “welfare pastor” who distributed food and clothing to the poor, Havlicek notes.

As Vincent’s zeal for Christ grew in his early twenties, he wanted to study theology, but failed his entrance exam for seminary. Instead, he went off to serve as a missionary to coal miners in the Borinage district of Belgium.

He found miners who were sick and starving, living a bleak existence, without adequate food, water or warm clothing. A mining explosion had left many in a horrible condition. Fighting for survival, they apparently had little interest in his evangelistic appeals.

In response to their plight, Vincent gave away everything he owned, including most of his clothing. To tend to their medical needs, he ripped up his own bed sheets for bandages, and slept on straw on the ground. “By such actions he won the admiration and respect of the workers, and was able to convert some of them,” Havlicek notes.

|

| The Sower, 1888 |

“Vincent was a very generous man. He understood that unconditional love of God extended to unconditional love for others. He would never recognize love that was not an action.” Van Gogh was also inspired by the writings of Charles Dickens in his compassionate response to human suffering.

Sadly, a church committee overseeing Vincent thought he suffered from excessive zeal and fired him because he did not dress or preach eloquently. “It did not seem to matter to them that he literally poured out his life in sacrifice and service on behalf of the diseased and destitute,” Havlicek laments.

Vincent went home to his parents, but the physical and emotional ordeal of caring for the miners and the rejection by the church hierarchy had taken its toll. He appeared to suffer a nervous breakdown, which caused his father to make his first quiet inquiries about committing Vincent to an asylum.

|

| Pieta, 1889 |

At the same time, the drawings Vincent had made of miners and others captured his brother Theo’s interest. He persuaded Vincent to begin formal art studies at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Van Gogh wanted to continue to serve God with his art, stating: “…to try to understand the real significance of what the great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces, that leads to God. One man wrote or told it in a book, another in a picture.”

In 1881, he fell in love and proposed marriage to woman who was seven years older. She turned him down, but his advances persisted in a clumsy manner. Exasperated, the woman and her parents forcibly rejected Vincent, partly due to the struggling artist’s inability to support himself.

During the time Vincent lived with his family, Vincent and his father got into more and more heated arguments. After one particular violent exchange on Christmas day when Vincent refused to go to church, Vincent left to live on his own in The Hague.

The following year Vincent attempted to rescue a prostitute, Sien Hoornik. He wrote of his unusual relationship with Hoornik in his letters: “I met a pregnant woman, deserted by the man whose child she carried. A pregnant woman who had to walk the streets in winter, had to earn her bread, you understand how, I took this woman for a model and have worked with her all winter. I could not pay her the full wages of a model, but that did not prevent my paying her rent, and, thank God, so far I have been able to protect her and her child from hunger and cold by sharing my own bread with her.”

|

| The Good Samaritan, 1890 |

As one might imagine, his family was shocked he had taken in a prostitute and pressured him to alter his living arrangement. His parents continued to explore the idea of committing Vincent to an asylum due to his errant behavior.

Vincent’s father died of a stroke in 1885 and Vincent’s sisters blamed him for “murdering” his father, due to the emotional fallout from their intense discussions and unresolved conflict.

After his father’s death, Vincent went into a tailspin. “Vincent embarked on a three-year drinking binge in Paris,” Havlicek notes. “This was the most destructive period of his life. Even so, he continued to produce some remarkable work inspired by the Impressionists who exhibited in the great city.”

He experimented with absinthe, which was a highly popular drink in some circles made from unstable wormwood alcohol. The unpredictable side effects for many users included nerve damage, blindness, and insanity. Absinthe may have triggered the epileptic seizures that began to plague Vincent during this period.

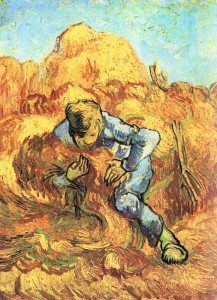

|

| The Shief Binder, 1889 |

“After drinking a large quantity of absinthe, Vincent slashed off a portion of his ear,” Havlicek recounts. “It’s possible he had a grand mal seizure when he slashed the upper part of his ear,” he says.

Most art critics and historians believe Vincent lost his faith sometime between 1882 and 1885. Yet Havlicek found abundant evidence in Vincent’s letters and his art that an abiding faith remained, even as his health and behavior deteriorated. Surprisingly, most of the Christian-themed paintings appeared in the last three years of his life.

For the sake of self-preservation, Vincent moved to Arles in southern France, where he had an unusual meeting one day in a café he frequented. A local peasant walked in who bore a striking resemblance to his deceased father. “This chance meeting led to some of the most emotionally wrought portraits in the history of art – a father’s posthumous portrait painted vicariously using the face of another,” Havlicek notes.

|

| Portrait of a Peasant, 1888 |

Vincent painted the man’s hands clasped as if in prayer, holding a shepherd’s staff. “He surrounded his father in a gold light, which is always a symbol of the divine,” Havlicek notes. “It’s a sacred work; Vincent loved sacred references.”

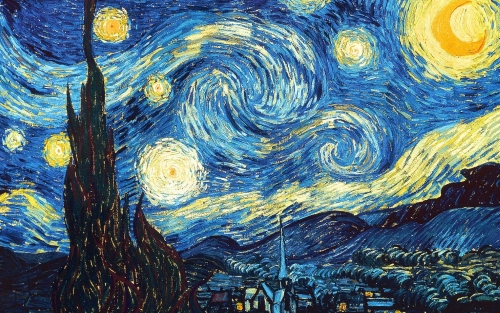

Havlicek made the significant discovery that a saintly bishop’s ruminations on the cosmos in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables inspired one of Vincent’s most famous works, The Starry Night:

Victor Hugo wrote, “He was there alone with himself, collected, tranquil, adoring, comparing the serenity of his own heart with the serenity of the skies, moved in the darkness by the visible splendours of the constellations, and the invisible splendour of God, opening his soul to the thoughts that fall from the Unknown. In such moments offering up his heart at the hour when the flowers of night inhale their perfume, lighted like a lamp in the centre of The Starry Night…”

|

| The Starry Night, 1889 |

Vincent used the same title for his painting and Havlicek notes the striking similarities. “The theme of Les Miserables is redemption,” Havlicek observes. In van Gogh’s painting, “the stars are painted like flowers. There is an interaction between the earth and heaven. It is as if heaven is reaching down.”

“Starlight implies in Vincent’s view that the darkness of sin, guilt, and death are overcome by divinely mediated grace.”

“Van Gogh’s interest in the Gospel is very profound,” Havlicek says. His paintings, The Good Samaritan, The Raising of Lazarus, The Sower, The Sheaf Binder (or harvester) all display Christ-centered themes.

Havlicek even sees the work of Christ in van Gogh’s famous painting of sunflowers. “In 1886 van Gogh found sunflowers thrown in a street gutter in Paris. He went home and painted these beautiful cast-off flowers. The way the flowers were transformed through love shows redemption.”

|

| Four Cut Sunflowers, 1887 |

Van Gogh died under unusual circumstances in what most label a suicide, but Havlicek has some doubts. “No gun was ever found,” he says, and there were no powder burns near the fatal wound to his abdomen.

Two boys admitted they were target shooting near van Gogh and had an encounter with him that appears suspicious. “One wrote a confessional letter years later Vincent lingered for two days after the fatal shot. When he was interviewed by police, Vincent said, “I’m hurt but don’t blame anybody else.”

Havlicek believes that if he was shot accidentally by the boys, it was consistent with Vincent’s character to withhold that information. “He had a very sacrificial aspect to his personality. There were several times in his life when he took the blame for someone else,” he says.

“He loved Christ enormously at the end of his life,” Havlicek maintains. “He said Christ alone among all the magi and wise men offered men eternal life. In spite of a broken life, something glorious emerged.”

Dr. William Havlicek has over 30 years of experience in college teaching, museum administration, publishing and fine art/studio production and exhibition. He holds a Ph. D from Claremont Graduate University. He currently teaches at the Laguna College of Art and Design in Laguna Beach, California. Proceeds from the sale of his book are donated to PROGENY, an international organization dedicated to the rescue, treatment, and rehabilitation of exploited and endangered children and the pursuit of justice on their behalf.

Images from Olga’s Gallery